My dad didn't think my mum was a mistake

|

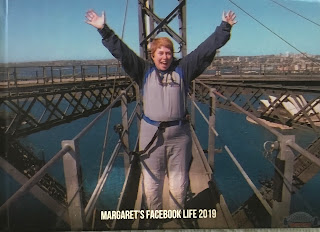

Freda in Dunedoo

|

My mother’s birth was not planned. In fact, she was a mistake, the result of two employees in a stockbroker’s house coming together maybe fleetingly, maybe not.

He was the butler in the Forbes’ household and she was the parlourmaid, both senior servants providing a comfortable lifestyle for a family of three. The stockbroker died later that year and must have been an invalid because two nurses were also employed as well as three other servants.

The stockbroker’s wife was born and grew up in St Petersburg, Russia but was of Scottish and English heritage. Their only son Nevill Forbes usually resided in Oxford as a Reader in Russian. He had spent quite some time in Russia whilst recovering from tuberculosis at his uncle’s specialist medical centre on the Black Sea. He was probably bilingual from an early age and later became the second Professor of Russian at Oxford.

Initially, I thought that Nevill was my mother’s birth father after my mother’s half-sister told me that her aunts in England described Freda’s father as the young man of the house.

So I made the mistake of going down that rabbit hole: it appeared to make sense, especially after a researcher in New Zealand told me he believed that Nevill was his grandfather. DNA testing later proved that neither of us was correct. I eventually found a close DNA link with an American resident who proved to be the great-granddaughter of the butler, Henry Edward Jones. Henry was a similar age to his master’s son Nevill but was very much a similar class to my birth grandmother, Kate Palmer. However, he was a married man with a wife and two children living in the same village and in no position nor desire to acknowledge another servant’s baby.

It seemed a sensible solution- at least for the butler but maybe also for the wealthy employers to remove Kate (known as Kitty in Australia) from the village. Someone - possibly her employers - provided her with a travel trunk with her initials inscribed and escorted her to Antwerp where she boarded a steamship to Sydney on Christmas Eve 1911. She arrived in Sydney at the height of summer at the end of February but it must have been a cold reception since she knew no one.

My mother, born on 5 June 1912 was immediately promised to a farmer’s wife who had delivered a still-born son and was soon taken by train to Dunedoo in the central west of New South Wales.

Freda found out that she was "adopted" at the late age of 18 when her mother told her it was time she left home. It was a shock and she had mixed feelings about it since she didn't have a great deal of respect for her adopted mother. The latter 'ran around town' a bit too much for teenage Freda's liking and she felt badly for her adopted father, a kindly man.

Learning who her birth mother was, she spent a weekend meeting Kitty and her new family. However,

before leaving, Kitty told her that "it was nice meeting you dear but I don't think we should do it again."

So at age 18, Freda felt rejected twice over. Nevertheless, in her local town, she was befriended by some warmhearted people, including the local Anglican rector and his family of girls. When she married my father in her early 30s, this family hosted her wedding reception.

As I grew older, I realised that my mother sometimes had a "chip on her shoulder" but at the same time. having received kindness when she needed it, she handed it out in spades. My childhood friends always remember her with fondness as do many of the neighbours' families.