|

| Agricultural labourers |

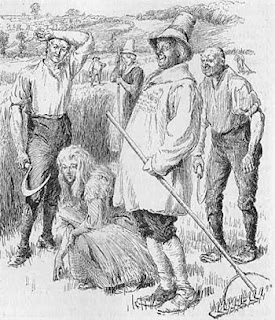

In 2011, in another blog about my Tucker ancestors, I wrote about my 3x great grandfather George Tucker 1802-1886, calling him the ancestor I felt most sorry for. He was born in the wrong county, in the wrong era, and at the wrong end of his family. By the time he was of working age, drought had overtaken Wiltshire, farmers were reducing manpower through the use of machinery and the parish of Downton had organised a shipload of parishioners to migrate to Canada. George Tucker was not amongst them. He eeked out a living as an agricultural labourer and woodsman, unlike his Tucker ancestors, many of whom were men of substance. By 1881, he was livng in the Union Poor House at Alderbury and died there in 1886.

He and his wife Hannah (nee Isaac) had four children, two sons George (b. 1832) and William (b. 1834), and two daughters (Ann b. 1829) and Mary (b.1840). They lived in the rural district of Hamptworth where there was a pub but no church. Whilst the two girls married local lads, neither son could see a future for himself on the land and there cannot have been many opportunities for illiterate young men in either Downton or Landford, the two closest villages they could walk to. In 1841, the family was split up with father George, his pauper mother, and two sons living on the land whilst his wife and two daughters lived at Landford Lodge, no doubt working as servants and sheltering from the cold. Mary was still an infant.

By 1851, the Tucker family was reunited in Hamptworth, except for younger son William. He was working as a farm servant for distant relatives in West Wellow, Hampshire. By the mid 1860s, William had moved to London where he was a fireman and later a stoker for the railways. He married a widow, Emma Garnett with three daughters and they had two more daughters together. By 1881, he had died, probably due to occupational hazards and poor living conditions in West Ham where they lived.

Meanwhile his older brother, George had moved to Southampton where there were abundant, if poorly paid, opportunities for work in the ever growing port. He married another immigrant to the town, one Sophia Jefferis from Fordingbridge in Hampshire.

George and Sophia Tucker were my great great grandparents and were the first of my Tuckers to live in Southampton. Another three generations did so until my father left for Australia in 1925 and his Uncle Bert Tucker moved to London a decade earlier.

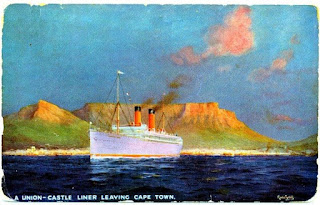

George worked on the docks as a coal porter and stevedore. No doubt the coal arrived from all over England and Wales via the railways. In those days, the Southampton terminus, completed by 1840, was at the docks. His working conditions would also have been poor but no doubt Southampton was a much healthier place to live than London because he lived until 1914.

|

| Upper Canal Walk aka The Ditches |

Sometime before 1861, George and Sophia moved to 9 Bell Street, adjacent to the thriving Upper Canal Walk, also known as the Ditches. They produced a son, George William (1856-1924) and two daughters Louisa (1860-1879) and Ellen Jane (1869-1948). After George’s death in 1914, Sophia remained living there until her death in 1922. So she was there for over 60 years, looked after in her later years by her daughter Nellie McInnes. They would not have owned the house but could have had a long term lease.

This generation of Tuckers had truly branched out, leaving behind their rural lives and personified the industrial revolution which continued to build great wealth for the British empire, if not for themselves.

However, George and Sophia Tucker lived long enough to see their only son become a very successful music dealer and give his own boys a good education and sporting life.